Unsure of where you sit politically? The Political Compass Test might offer some guidance. It’s the ideal thing to sit on an eventless Tuesday night – there are loads of questions, they cover topics ranging from economics to sex, and the end result is pretty cool: your political stance is displayed on a 2-d quadrant, which you can print out and stick on your wall, if you’re on the more obsessive side (which I’m not, of course).

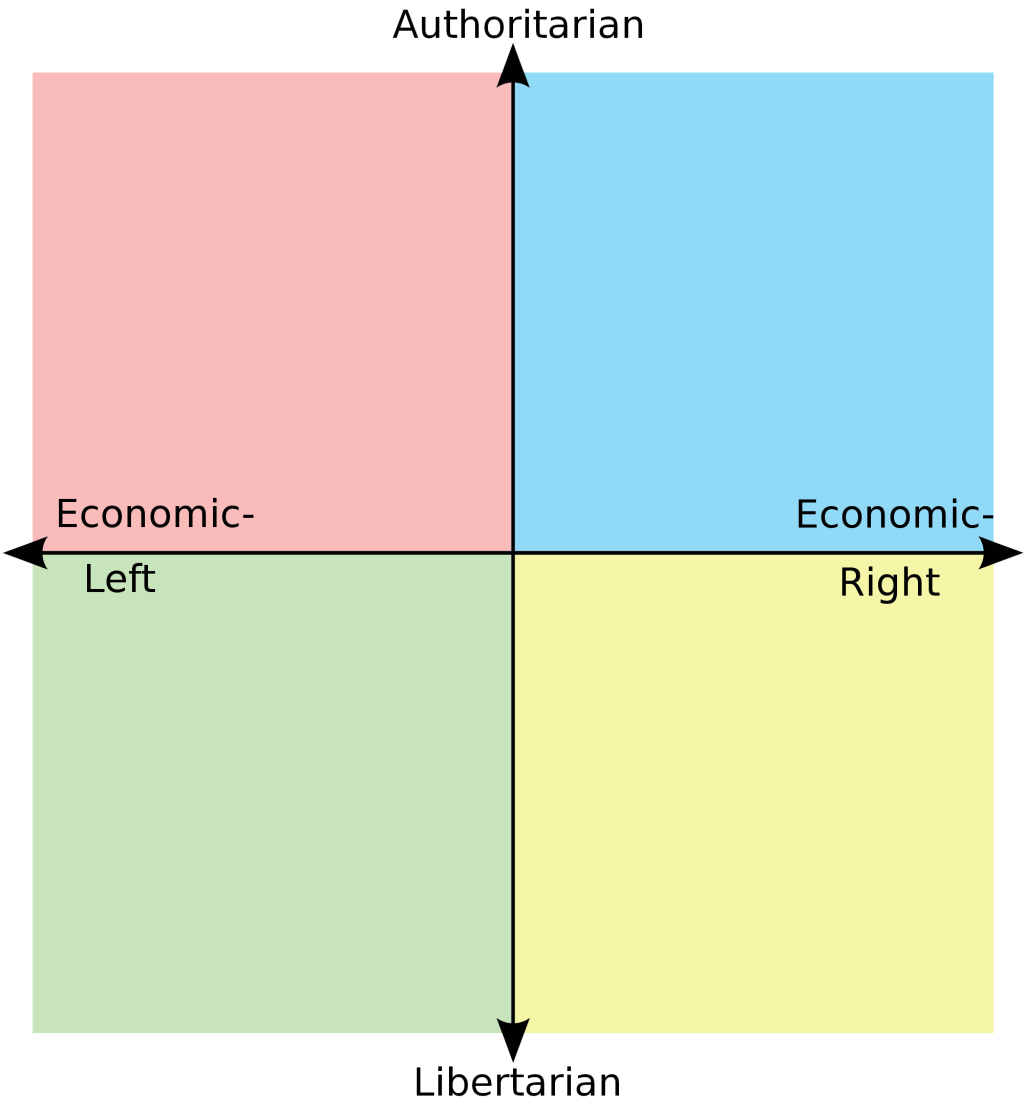

For those of you unfamiliar with the test, here’s how the 2-d quadrant works. Your position on the x-axis marks where you stand on the capitalism-socialism debate – the further right you are, the less government intervention into economic matters you favour, but the further left, the more. (Any good Marxist should already see a problem with this). Your position on the y-axis, meanwhile, is where you sit on social issues. The further you go up the axis, the more Authoritarian you are on all thing’s abortion, homosexuality, drugs, and parenting. So, if you come out in the bottom right of the quadrant, it means you favour market economics and are socially liberal, whereas someone in the top left leans away from capitalism, though also isn’t a fan of immigration, homosexuality or drugs. Despite it being a fun test to take, I think it’s actually highly inaccurate, especially on the economics axis. I have 3 problems with the test’s evaluation of economic ideology.

Number 1: the test contains some heavily loaded questions

The first question on the test is “if globalisation is inevitable, it should primarily serve the interests of humanity, not corporations – strongly agree all the way down to strongly disagree?”. “Did Bernie Sanders write this test?”, muses a frustrated Ben Shapiro. He is right. The question tacitly implies that free-market economists favour corporate interests in the ostensible trade-off between corporate money-making and human welfare. This ignores basic market theory – in a free-market, competitive economic pressures mean that corporate capital has to be used in a way which benefits humanity, whether through producing innovation, lowering prices, or raising wages. Moreover, the theory states, market forces are more efficient at improving living standards than redistributionist measures, for many reasons expounded in the public choice literature. Hence, openness to corporate investment by developing countries has been a huge force for good. Papers continuously suggest that sweatshop workers employed by multinationals enjoy a significant wage premium; and that globalisation itself has done a tonne of good for poverty reduction, child labour, and infrastructural development.

Another question which I’d say is loaded is “because corporations cannot be trusted to voluntarily protect the environment, they require regulation”. This is a stupid basis on which to assess someone’s aversion to government regulation. In fact, environmental regulation is probably the kind which is most favoured by free-market economists, as it is designed to limit negative externalities, stuff you can easily characterise as violating the Non-Aggression Principle.

Number 2: the test assumes all government intervention is the same ideologically

“The more the government does, the more socialister it is”, reads a famous meme making fun of Turning Point USA. Essentially, a popular right-wing characterisation of socialism is that it is defined by its rejection of market economics, meaning any form of government intervention is socialism. That’s logically equivalent to saying that since cats and dogs are both animals, cats and dogs are the same thing.

Anyone vaguely familiar with socialist teachings will know the matter’s far more complex than this. Socialism is the abolition of capitalist institutions – namely, private property – for the sake of allowing workers to control the means of production, permitting the dismantlement of Bourgeois exploitation. To phrase it differently, socialism necessitates state intervention for the sake of economic equalisation/redistributionism. But the way the political quadrant is constructed assumes that anyone who would sit on the left of the axis because of rejecting market economics accepts this. This is incorrect: you can hate capitalism while at the same time rejecting what socialism aspires to achieve. Let’s look at a hypothetical example, then two real-world ones.

Suppose the state chose to spend 100% of GDP on the military, corporate subsidies, bank bailouts, establishing a global empire, and buying Elon Musk more mansions. We can safely say that everyone on the right of the axis would object to these policies, as they absolutely represent an impingement on the free-market order. But placing this hypothetical government on the left of the axis would be tricky, to say the least – no socialist, who undoubtedly does reside on the left, would see much commonality with them. Those policies clearly repudiate the aim of economic equalisation, and just attempt to provide more power to the ruling class.

It’s just obvious that one cannot frame economic policy in terms of a dichotomous, left-right spectrum, as there are lots of different economic systems which involve rejecting market principles, yet can’t be identified as ‘left-wing’ or socialist. Let’s proceed to our two real-world examples.

First, the Nazi government, a textbook example of where people use a genocidal dictatorship to make their opponents’ views look bad. The right never shuts up about the fact they incorporated ‘socialism’ into their name. The left, meanwhile, takes a much more academic (but equally dumb) approach, arguing fascists were agents deployed by the elites to prop up a failing capitalist order. But the Nazis’ policy record really shows that they fit neither description, as it contained a messy mix of both pro-market and anti-market policies.

On the pro-market side, many industries were privatised, labour unions were dismantled, and tax cuts were implemented. On the anti-market side, hefty price controls were imposed, banks were essentially prohibited from investing in smaller businesses, high tariffs were implemented, and the rule of law was basically suspended to enable the expropriation of Jewish assets. Where, one must ask, would we place the Nazis on this test’s economic spectrum? Even if, on net, the Nazis militated towards anti-market economics, very few socialists would be happy with being placed on the same side of the spectrum as genocidal anti-egalitarians! After all, the Nazis used their anti-market principles to reinforce hierarchy, not abolish it, by delegating greater power to the ruling class through explosive military spending and asset expropriation.

A second example is Apartheid South Africa, where the government needed to heavily suppress market forces to sustain vast racial inequalities: the 1913 Native Lands Act legally reserved only 7% of the country’s land to Black people. More racist legislation followed, such as Pass Laws, which largely prevented Black people from moving into the cities, guaranteeing mining and agricultural companies a monopsony over labour in underdeveloped rural areas. Clearly, the Apartheid government wouldn’t appear on the Right of the economic spectrum in our test, as it wholeheartedly rejected free-market principles. On the other hand, leftists/Marxists wouldn’t be happy with the Apartheid government sitting in their boat, either, as deliberately creating a system through government intervention to make Black people the slaves of corporate capital clearly violates the socialist objective of the dismantlement of Bourgeois power.

To sum it up as simply as possible: not all instances of government doing stuff can be equated ideologically. To represent economic beliefs with a linear spectrum is therefore idiotic.

Number 3: the test neglects motivations for beliefs

The previous problem I just highlighted indicates that vastly different policy prescriptions can’t be placed in conjunction with one another. But another problem with the test is that it can’t compute the possibility that two people can support exactly the same belief for vastly different reasons – so different, that placing them in the same ideological camp just wouldn’t make sense. There are tonnes of examples of this.

The first is free trade: both a Marxist and a far-right nationalist may oppose the globalised trading system, but for completely different reasons – a Marxist, on the belief that globalisation instantiates the capitalist exploitation of labour and resources in developing countries. A far-right nationalist, meanwhile, hates free trade because to them it threatens the ethnic superiority of the West by deporting jobs and capital to non-white countries. As we can see, a Marxist opposes free trade on egalitarian grounds, whereas the nationalist opposes it on anti-egalitarian grounds. Can we really say that they are ideologically aligned? At least, that’s what the test would imply, because it does not investigate why we believe the stuff we do. It simply asks us to state how much we agree or disagree with certain propositions.

The second example is environmentalism. Support for the environmental cause is something certainly associated with the left, who argue that our environmental problems are symptomatic of unrestrained capitalist profiteering. At the same time, few know that the environmental cause has been hijacked by far more sinister political movements – namely, the far-right. The belief that the planet totters on the brink of environmental collapse has been awfully convenient to right-wing extremists, giving oxygen to terrible notions of racial dynamics. Of course, these two different kinds of support for the environmental movement may well lead to dramatically different policy prescriptions – one may recommend regulations to limit environmental externalities, while the other might suggest genocide. A test could uncover this with deeper questioning. But most political ideology tests tend not to get too specific with this kind of motivational detail, so it goes to show that support for broad beliefs can’t always be correlated with ideology.

It would be the worst thing if someone actually adjusted their voting behaviour based on this test; if a socialist, placed on the left of the economic axis, came to support all forms of anti-market policies, even when they clearly simp for the Bourgeoisie – tariffs, bailouts, subsidies, and more. This would create a homogeneous block of everyone who opposes markets, producing an unruly alliance between the left and certain brands of right-wing extremism. As a result, this would grant legitimacy to some of the worst people in society.